This is why distributed systems are useful (and I am building one)

In this post I’d like to discuss the concept of distributed systems (DS) starting with the question of what makes a bunch of computers a system. What can be achieved by designing such systems, and what are the unintended benefits? When is it required to build one? I will touch briefly on some of the challenges, but my main focus is on the motives for creating DS and why I think it is worth the investment. While working with web-scale systems and critical high-availability service, I had to explain some of the aspects of these systems to new engineers joining a project. Now the time has come for me to design my own distributed/grid computing system for my machine learning project. I think it is worth an attempt to explain DS and the motivations for it in a more or less coherent post. Here it is…

What is a distributed system?

A brief note on computations

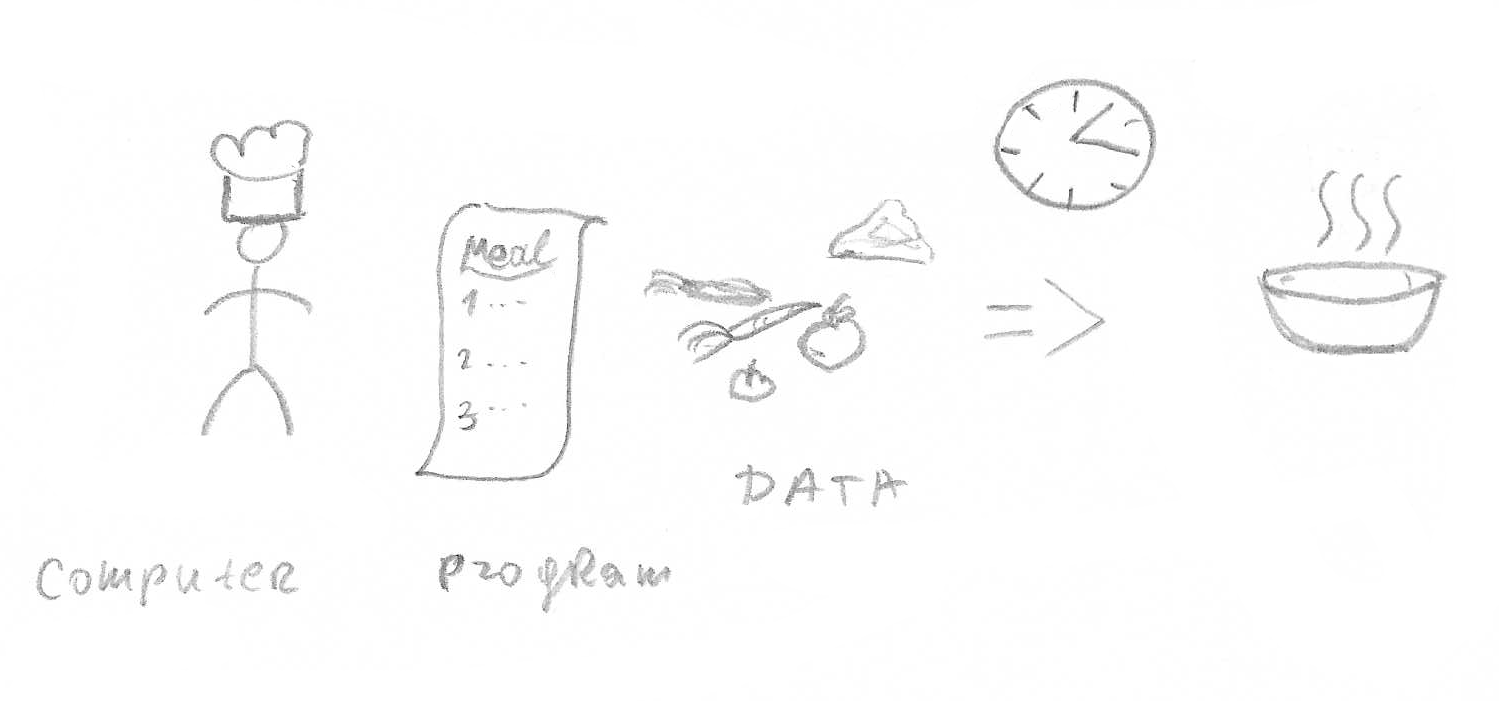

Software engineering can, at some level, be viewed as an art, in which computer programs are created to solve problems. At this level, a program is just a serious on instructions not unlike a recipe for a meal. Just like with recipes we are interested in results not in the actual actions. The only issue is someone needs to follow these instructions in order to make an actual meal. In case of a computer program, an entity executing instructions is called a computer.

The ‘cooking process’ of transforming data into results is called computation.

A simple meal can be prepared by a single person, but an elaborate banquet for many guests might require many cooks for it to be done in time.

The ‘cooking process’ of transforming data into results is called computation.

A simple meal can be prepared by a single person, but an elaborate banquet for many guests might require many cooks for it to be done in time.

And so is with computer programs – it can be run by a single physical machine, a laptop, or a phone. Depending on the problem being solved, more than one computer might be required, in which case we would call the group of computers a system. These machines might sit on your desk, or the computer system might live in different data-centres spanning the globe. And the computers themselves might not even be real, but virtual machines. I’ll talk about the general engineering principles of such virtual systems.

And so is with computer programs – it can be run by a single physical machine, a laptop, or a phone. Depending on the problem being solved, more than one computer might be required, in which case we would call the group of computers a system. These machines might sit on your desk, or the computer system might live in different data-centres spanning the globe. And the computers themselves might not even be real, but virtual machines. I’ll talk about the general engineering principles of such virtual systems.

As for kinds of problems being solved, it varies. I like to think that we, as software engineers, focus on important issues, which is why we must ensure that good practices are developed and employed. I will leave the topic of specific problems for a different post and instead focus on engineering principles that can be employed.

For the purpose of this post, I consider a computation problem to be the transformation of some input, usually known as DATA, into output or results by a computer program. The key here is that the same program can be used to transform different inputs into different outputs, so a number of the same programs can be executed independently.

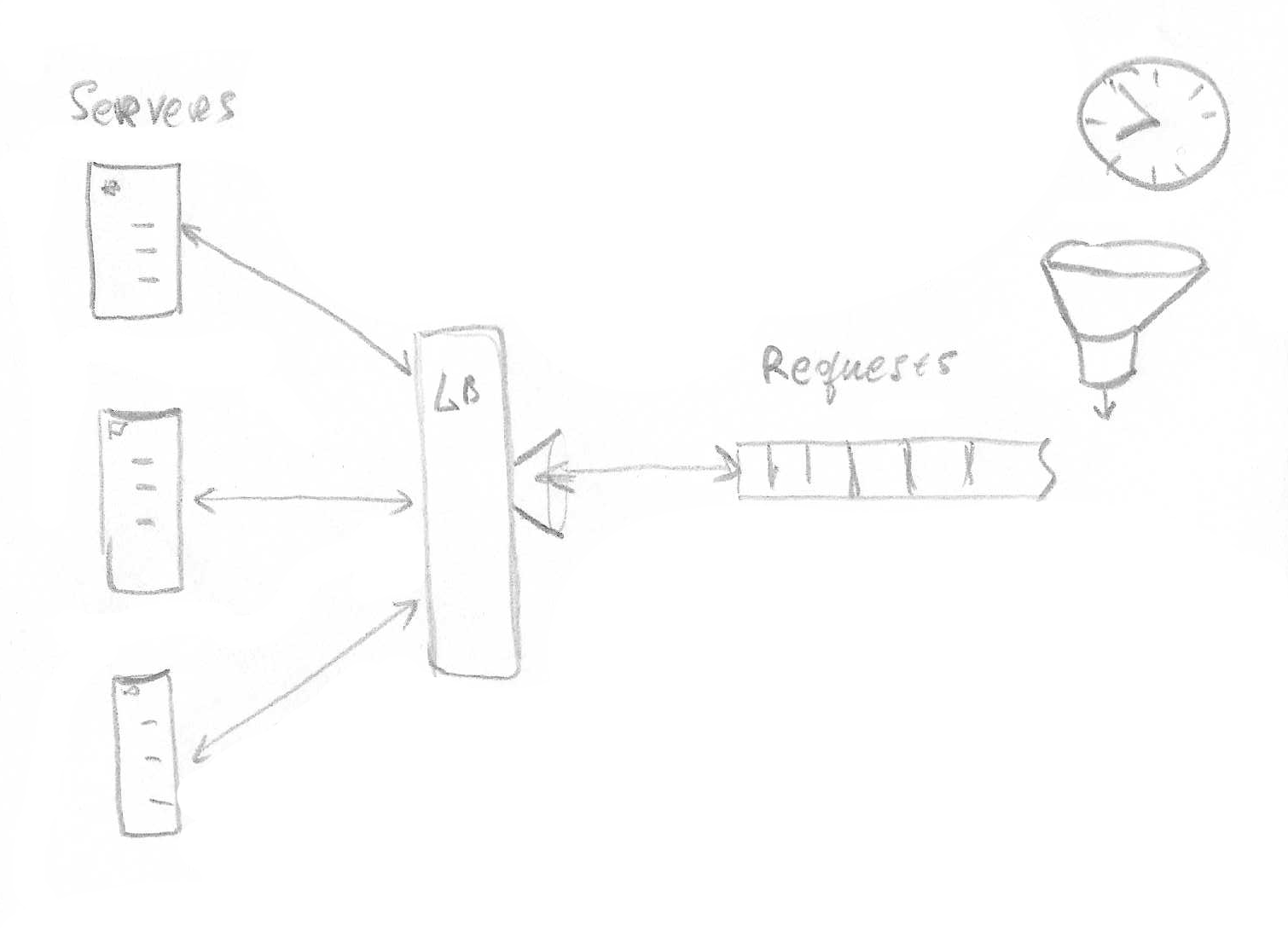

This concept of IO and transformation is important for understanding different types of problems and how they influence the design of transforming systems. For example, if input data is relatively small, as in the case with an HTTP request, and fits into a single machine memory, one machine is sufficient for data processing. In this case, a DS might be required to fulfil many requests simultaneously. And if there are so many requests that there can be no single machine powerful enough to handle all the traffic – we call it a web-scale problem. An essential characteristic of this type of systems is that data processing is distributed in time.

Not all requests arrive at the same time. Instead, each node of the system is conceptually processing one request at a time. Multiple nodes can process requests at the same time speeding up overall request throughput. This way capacity of the system to process requests grows linearly with each added node. That is, in theory at least. Linear growth is only possible if all requests are independent and network scales with a number of nodes.

Not all requests arrive at the same time. Instead, each node of the system is conceptually processing one request at a time. Multiple nodes can process requests at the same time speeding up overall request throughput. This way capacity of the system to process requests grows linearly with each added node. That is, in theory at least. Linear growth is only possible if all requests are independent and network scales with a number of nodes.

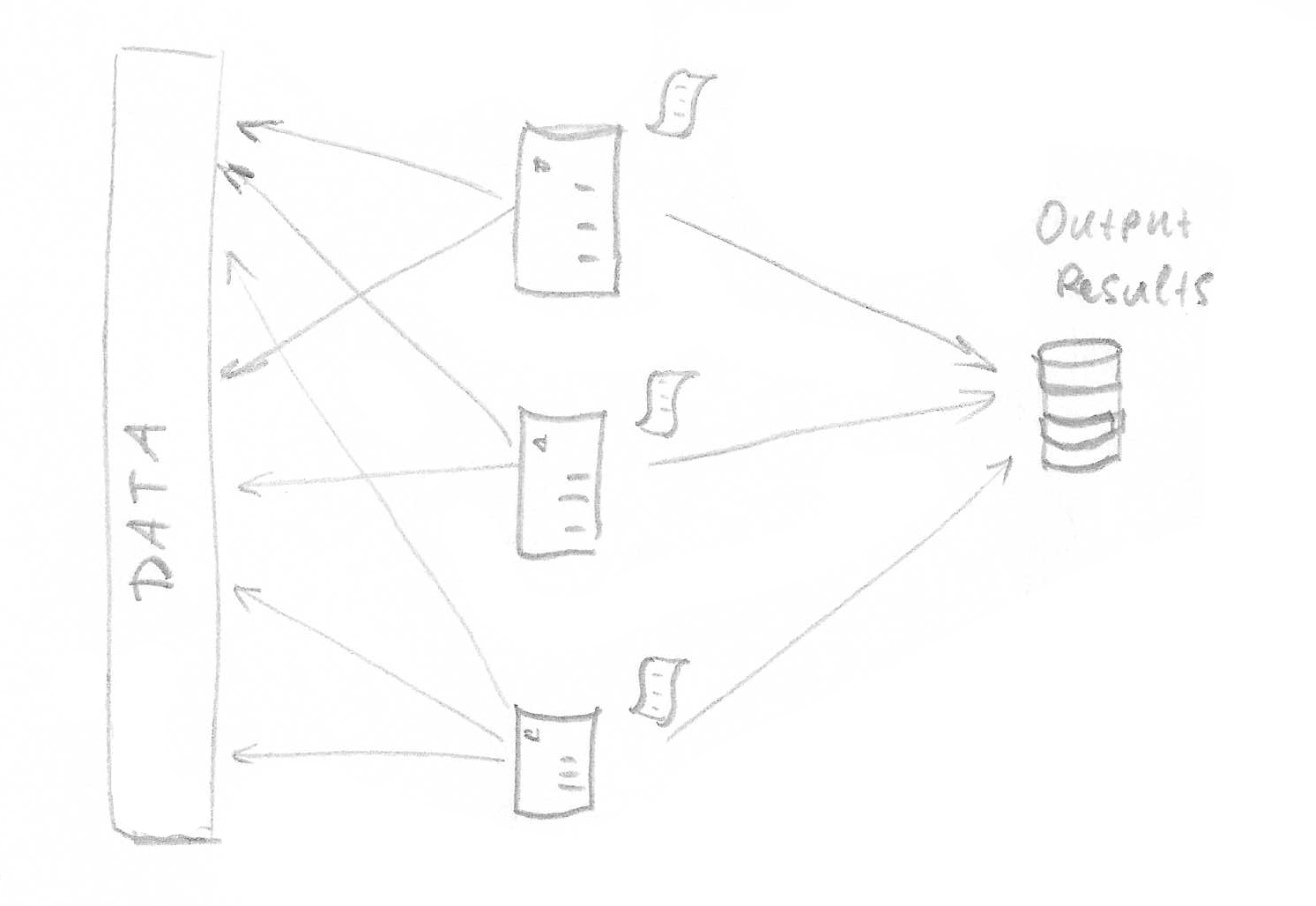

A very different system might be required when a whole data needs to be processed at the same time but does not fit into single machine memory. In this scenario, DS might be conceptually imagined as a distributed memory substitute for data distributed in space.

There is yet another case, in which data may fit into the memory, but the transformation process is slow. To complete overall data processing, more computers are added.

There is yet another case, in which data may fit into the memory, but the transformation process is slow. To complete overall data processing, more computers are added.

Depending on the problem being solved, one might need a distributed system, whether it be distribution in space, time or both. These are some fundamental requirements that enable a set of computers to work together.

What makes a bunch of computers a system?

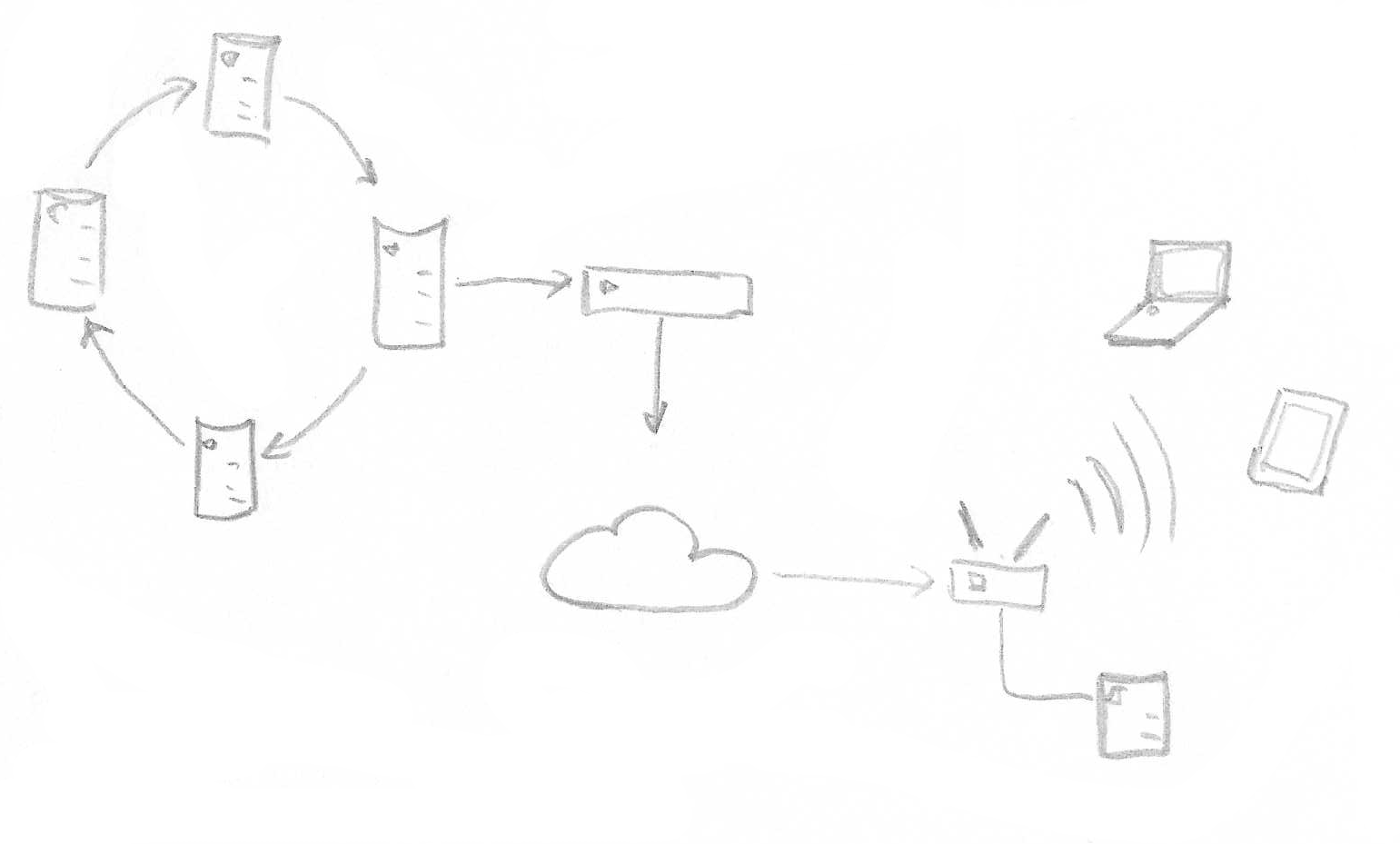

A bunch of computers are considered a system only if they are solving a problem. Which computers do by running a program that operates on data in computer memory. Therefore a bunch of computer solving a problem means that there some data (maybe partial) for the same problem. It is not required for computers to run the same program or to have exactly the same data. However, for them to work on the same problem and thus be in a system – programs executed by individual participants must be related, or data should belong to the same problem. This implies some form of communication, maybe between a client of the system and the servers. Servers often talk to each other, and at the very least one server needs to give the computers a task and collect results. More formally:

A distributed system is a set of independent computers (called nodes) interconnected to collectively participate in problem-solving.

(In theory, a collection of 0 or more elements is a set. In practice, it proved difficult to run programs that solved anything with 0 computers, which is why 1 or more compute nodes is required in a system, which can make meaningful progress towards a solution.)

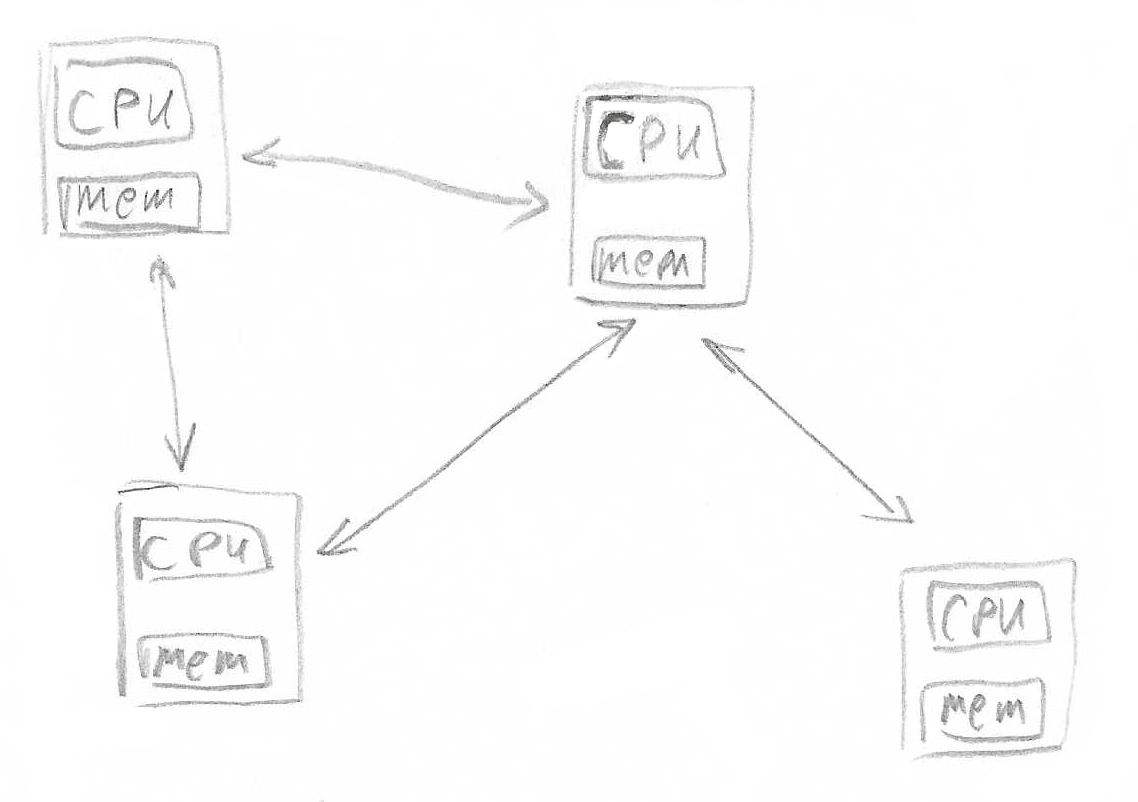

This definition highlights what makes distributed systems important and challenging at the same time: The computers are independent. Distinct computation entities run at their own pace with their own compute and memory resources. Note that it is not expected that computers be separate physical machines. Only criteria are for machines not have shared memory. This is why a 32 core machine not a DS as all cores have access to the same memory. At the same time, 32 virtual machines running on the same physical 32 core machine but not sharing memory – is a DS. Having an independent component means they make progress independently of one another. They can start, stop, and fail at any time and in any order. It also means there is no shared memory between components. Depending on how this independence is taken into account, designed systems will have different properties. We will discuss the options and challenges later.

Communication is key

To make sure that all computers solve the same problem and don’t step on each other’s turf, they must work collectively; a bunch of computer doing unrelated things is not a system. And if one computer repeats work that was already done by another computer, there is not as much overall progress. Therefore, a degree of coordination is required. Coordination always requires communication, which for computers requires interconnection; in order to work collectively, nodes must be interconnected.

There are many ways to make computers talk to each other, not only on the physical level (Ethernet, DMA, WiFi, etc.), but also logically, which gives rise to various topologies with different characteristics.

Communication, however, is also the main cause of challenges within distributed systems. No matter how fast interconnect is, it is still slower than local memory access, which means latency is one aspect of DS that requires management. If there is too much communication and it is inefficient, the DS’s performance will suffer, potentially to the point that it is no longer a viable solution.

The other problem with communication is that it can fail. In local systems, if we can’t access the local memory, there is nothing left for software to do but to crash. DS, on the other hand, must be designed with communication failure in mind because it happens often. The software must also account for the healing process to ensure the system is dynamically re-balanced as communications with parts of the failed system come back online.

There are, of course, much more challenges than that, such as consistency, ordering, and monitoring, just to name a few. I’ll need to write a separate blog post to give them a proper overview. For now, let’s examine when we need DS and when we don’t.

What problems are best suited for DS?

Not all problems benefit from multiple computers. Engineering is required to design solutions that can be distributed. There are a number of ways to approach the design depending on the task. For example, a distributed system can be designed to solve many similar small problems – small in the sense that it can be solved by an individual computer but there are just too many of these small problems. Fundamentally, it is not unlike a time-sharing system, and examples include web applications serving web pages. Each individual page is usually easy enough for a single computer to produce. Still, a single machine might not suffice to serve web-scale traffic with hundreds of thousands of requests per minute (I am personally familiar with systems that struggle with only dozens of requests per minute). This class of problems requires distribution of incoming requests or jobs to process page requests, among a number of participating nodes. We can imagine a queue of such jobs waiting to be picked up for processing.

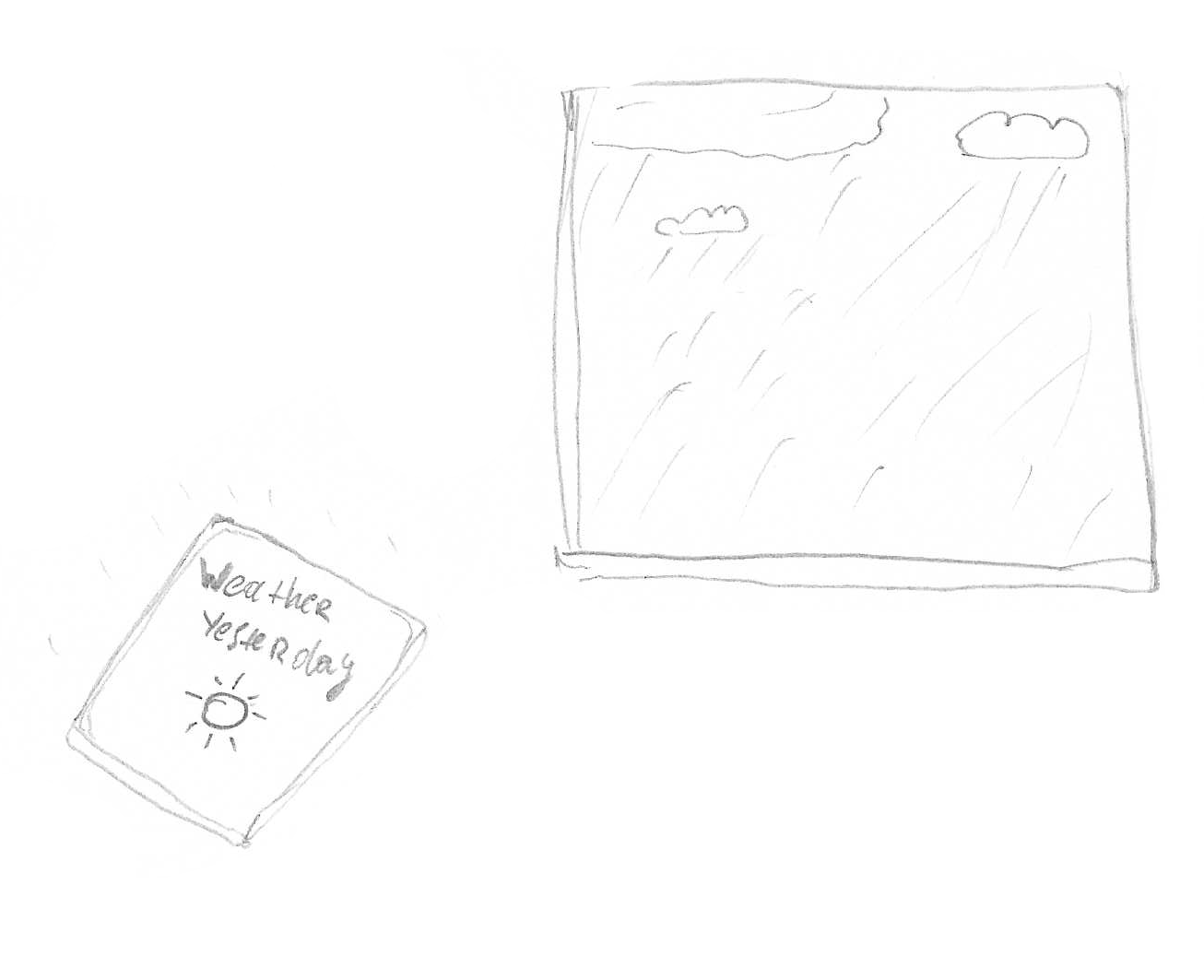

Another class of problems for distributed systems are single large jobs – large in the sense that a single computer might not have enough resources to solve it in a feasible timeframe or even fit all the data into its memory. Photo-realistic ray-tracing rendering used to be a popular example of this problem, but modern video cards mostly alleviated the issue. Instead, these days we talk about “big data” problems. One computationally challenging example is weather modelling and forecasting, which requires an astounding share number of parameters and a high resolution of modelling just to produce meaningful results. Surprisingly, a single computer (of the time of writing) can be used to model weather and make forecasts for the entire planet. The only issue is it takes a really long time, potentially weeks, to produce. By then, the forecast will not be very useful.

This is important to consider when designing a distributed system; even big data problems can be solved by a single machine using engineering techniques for memory by treading off performance. And for some really important problems, timely results are critical. Weather forecasting must be complete before the date of the forecast. Traffic routes must be computed timely to ensure traffic flows. And for an autonomous vehicle, decisions must be made in milliseconds to avoid collisions. One important observation here is that most problems in which solutions are used for real-world applications must be complete before a deadline, which depends on the problem and can range from days to nanoseconds.

This is important to consider when designing a distributed system; even big data problems can be solved by a single machine using engineering techniques for memory by treading off performance. And for some really important problems, timely results are critical. Weather forecasting must be complete before the date of the forecast. Traffic routes must be computed timely to ensure traffic flows. And for an autonomous vehicle, decisions must be made in milliseconds to avoid collisions. One important observation here is that most problems in which solutions are used for real-world applications must be complete before a deadline, which depends on the problem and can range from days to nanoseconds.

Personal motivation to build DS

I personally find DS fascinating. We interact with these systems daily; all payment processing, transportation, and even accessing the Internet you use to read this post rely on DS.

For a while now, I’ve been playing with the idea of building my own DS for a machine learning application I have in mind. The one question I’m hearing again and again when I mention what I’m up to on the weekends is:

“Why do you want to build a distributed system?”

I think the actual meaning most of the time is:

“I’ve heard distributed systems are hard to design right and difficult to operate. Are you sure it’s worth the effort?”

This question better highlights the motivation for creating systems: the economy.

It all depends on the problem and its requirements. If there is a single inexpensive computer that is sufficient to solve a problem, go with it. Note that there is an implicit assumption that the size of the problem won’t change, meaning if we choose a machine that can handle all the data for our problem today, we believe that either size of our data and demand on our system will never change. Kind of like a system that never used or didn’t get popular. We assume that this same machine will be able to handle more data in the future as demand grows, or we can replace machine for a bigger one to match demand.

There are a lot of scenarios to consider, and good businesses always expect the demand for their services to grow. In some areas, more data means better results. This is why good engineering practice is to design systems with potential growth in mind.

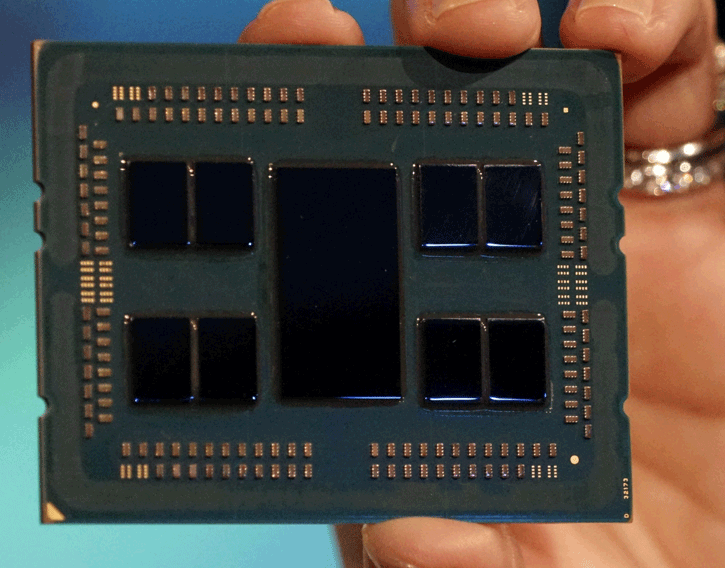

Of course, sometimes growth just means buying a bigger machine. The only issue is that bigger machines are more expensive, and there is a limit for how big a single machine’s CPU and memory can be.

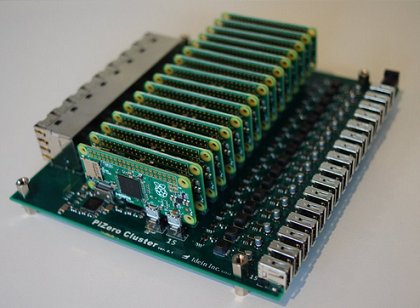

A different approach for growing compute power is to buy more machines and add them to your system. Scaling systems out is more efficient than scaling them up. For example, to get 64 cores you can buy a single CPU for $4000.  Alternatively, you can purchase 16x4 core machines, which are less expensive. In fact, 16 4GB Raspberry Pi 4s cost only $1,600, which also comes with 64GB of memory total. It is even cheaper if you buy compute modules at around $600.

Alternatively, you can purchase 16x4 core machines, which are less expensive. In fact, 16 4GB Raspberry Pi 4s cost only $1,600, which also comes with 64GB of memory total. It is even cheaper if you buy compute modules at around $600.

The downside, of course, is that all of these computers will need to communicate and will spend part of their CPU power doing so. Plus, you will need to manage traffic and membership, as computers can join and leave the system at any time. I do have a separate library to deal with dynamic group membership and failure detection, which I will introduce in following blogs, so stay tuned.

And speaking of failure detection… A light-hearted definition of DS by Leslie Lamport:

“A system is one in which the failure of a computer you didn’t even know existed can render your own computer unusable.”

His definition highlights an interesting property: failure tolerance. When dealing with a single-component system, a failure of this component is equal to a failure of the whole system. (Think of comments typed on your phone before you send them. If your phone were to explode, no one would ever know what you typed. A single component is your phone with comments.) However, there is an option to design multi-component systems in such a way that a failure of a single component does not render the whole system unusable. Think about your phone with unsent comments failing – it doesn’t mean that this blog should become inaccessible to everybody. There is a chance for someone else to hear that falling tree in a forest. :) And for this option, which takes some deliberate effort to realise, distributed systems are worth considering.

Keeping failure isolated to a single failed component has another advantage: maintainability. It is worth noting that in some respects, taking one component out for service (such as rolling out an update) is the same as failing this component. The main difference is that we take something offline for service intentionally and often with advanced scheduling, which reduces the impact on the whole system and its customers. On the other hand, failures that are out of our control happen whenever they please. The worst kind is when it is least convenient.

Conclusion

I hope this post provided a good overview of what distributed systems are and why we build them. The economy is definitely a significant driving factor for braving the challenges of designing such systems. As engineers, we not only need to solve critical business problems but do so economically. Sometimes that means solving it in a timely manner (as in weather forecasting). Other times it simply means that there is no single computer large enough to serve all the requests. Some of the side-effects of a well-designed DS may be requirements for your project. There is no way to have fault tolerance with just a single machine. In order to keep service online without interruptions during maintenance, some form of multi-component solution is needed. Of course, this post is only an introduction, and no discussion of DS would be complete without mentioning the fallacies of DS. I might dedicate a few posts to this topic later on, but for now, I’ll leave you with links to a very comprehensive discussion of that topic: