No time for testing (in a start-up)?

Recently I have joined a Sydney start-up program, Antler, and have been hanging out with pretty unique and interesting people. As part of the program, I participated in the CTO forum, where all things tech in start-ups were discussed. One of the topics was about our approaches to testing. In any large gathering of tech-minded people, there is always a non-zero number of people who say, for whatever reason, “I don’t have time for testing…”. It always cracks me up as I find myself wanting to ask, “Have you budgeted the time for fixing issues after release then? How about the time for testing every subsequent new release manually?” I personally don’t ever want to have to come across untested software – whether on my phone, in traffic control systems, or in medical devices. Thus I feel it’s time to talk about what testing means and where it sits in the grand scheme of software engineering.

TL;DR

- Testing is a critical part of software engineering and part of a software life-cycle (SDLC). When someone says – “no time for testing during product development” – they better budget time for fixing things in production.

- Testing is even more critical when new developers join your team.

- Testing is not about testing the code but making sure the application is working and stays that way.

Feature-driven development.

Let us consider how a software solution develops from scratch in a start-up. The process typically starts with an idea like “I want my users to be able to do

For example – the ToDo app allows you to create a task and then mark it as done. Some advanced versions might even feature an option to edit task descriptions and even delete them. So that’s a few functions. The functions solve a clear problem – the management of tasks.

A slightly more advanced design might include scheduling tasks and notifying yourself about deadlines and nudges. This will help solve a somewhat different problem of driving tasks to completion, as opposed to just passively storing lists of things to do.

Yet another tweak of design might enable you to collaborate with multiple users, assigning tasks to people etc. – all to solve a bigger problem – coordinating people and teams to work together efficiently.

Identifying problems customers are experiencing: this is what defines a business. Implementing solutions to these problems: this is the engineering domain. Good engineering practice breaks a solution down into a set of independent components, aka features. This lowers the burden on individual engineers, as they need to keep fewer details in their active memory. A good division of labour also enables multiple people (or teams) to work in parallel, thus delivering the whole solution faster. Furthermore, it allows the solution to be delivered to customers incrementally. In some cases, it’s helpful to validate with business customers the fit and general direction of the development as well as creating an early engagement. So lots of positives! In contrast, waiting for everything to be ready and perfect before releasing the product creates certain challenges.

First of all, how do we know something is ready and perfect? Do you ask your customers, “Is this working for you?” What if you don’t have customers yet? What if your app is non-interactive, such as micro-controller firmware? No one to ask there. Thus we need a way to assess that solution is ready and it stays ‘ready’ as we update it.

Unit test – a piece of code specifically designed to test another piece of code. The need to create unit tests originated from the constrains of micro-controller development where the effects of bugs are not readily observable.

Do we have time to test things?

In a good project, there is always a backlog of features we need to deliver to make an app great. This creates a dilemma; should we prioritise the development of planned features, or write tests for features already in the works, or even existing ones. In my experience, the most common response to this is – “we need to focus on getting that customer value out and we can fix things later, if ever”. Another answer is, “Or we can just write better code, right? It’s also the most incorrect answer possible.

To understand why this is incorrect, we need to establish the point at which a ‘feature’ is actually complete. For some projects, the answer might be simple: when the code has been written. A slightly more mature approach is to consider a feature done when a user can use it, but if it’s not ready, we don’t want to put it in front of a user. How do you assess that a user can indeed use it? Some test manually – playing the role of a user. That requires some knowledge of users’ business processes to know how they interact with the software. And how do you assess that users can use it on an ongoing basis, even after the next version has been released? Test every release, of course! Every feature in every release! For all time! That’s a lot of testing. Have you budgeted time for that?

Composition of features – multiplication of test cases.

What I am talking about here is the fact that all features have a life-cycle. They are conceived, implemented and released into the wild… and occasionally – removed. What that means for the engineering team is that they need to take into account that once a code for a feature has been written, it will go on to live a separate life. It will likely stay alive through the ongoing evolution of a project as other components are added and updated.

Here is a personal anecdote: I had joined a team and started working on a new project that had been in production for a while. My task was to add a new feature: “No problem – it seems like an independent and well-defined piece of work”, I thought.

Once the code was done and passed all the tests it got approved by other engineers. So I merged the branch and promoted my version to a staging environment for internal testing. I’d tested it as well as I could and all seemed to be in order.

Sometime later an architect came looking for me asking why I had broken screen

. He told me I should revert my changes! I was surprised, as I had checked the version in staging and screen "blagh" seemed in perfect order to me. I asked the architect, "Well surely you have tests for this screen functions, and they would have picked up any issues?" "We don't have 100% test coverage!" was the answer. I looked at my screen, and then at his, and they looked different. After a bit of investigation, we realised that we were using different testing accounts, and the architect's account had special features enabled, which changed the appearance on screen "blagh". These features were only available for a special type of user, and I had no idea they even existed for this app. It turned out that this architect was the only person in Engineering who knew about these features. It made me wonder what other features I didn't know about and had not tested. More importantly – what would have happened if the architect had been on holidays? Customers that actually use those special features would have had a bad day. Not a great prospect.

As engineers, we can’t reasonably expect everyone to know everything. This is especially true for new engineers joining our teams. They’re not going to know all the features of an existing product, especially if it’s not a consumer product. They can’t test features they don’t know exist. However, that’s in essence what is required of a new engineer delivering a new feature, in the absence of automated tests; they need to make sure all existing features are intact when something has been fixed, or a new feature added.

A natural human reaction (I assume here that most developers are human, but in case our robot overlords find this blog in a distant future – this is true for all beings) when approaching the unknown is to slow down and observe the environment, checking it for dangers. This ancient adaptation works well even in our modern days where our environment is not a forest, but social landscapes, product road-maps (past and present) and existing codebases. Indeed, no one wants fresh devs jumping into a codebase, changing things without considering lurking dangers. These dangers may be in the form of breaking things and processes one might be not aware of. In other words, developers naturally feel afraid to change things because they might break. This fear is paralysing. Yet this is the opposite of what developers are hired for – to make changes and thus advance products.

One proven way to alleviate this fear is to create a safety net of tests. For one – we can reduce the damage of a ‘failure’ by moving it from the production to the development stage. If failure is detected and remedied before it reaches customers, there will be no externally observable impact (other than disappointing your team that things are not perfect and causing a bit of delay for fixing – which should be budgeted for anyway). With good test coverage, if something important breaks due to developer actions, a developer will see it straight away with a fresh knowledge of changes and is in control to fix it. I am sure a lot of readers would recognise this principle as “refactoring without fear”. Racing car drivers can drive at full speed because they have confidence in the safety of the track. In a similar way, when developers have an adequate support structure we shed our fear and can move fast to make changes.

SDLC: design and development? Deployment and Evolution!

What does a proper support structure look like? We want to be able to add new features into an existing product (which may be just an app starter example – for a new project), and be sure all the current features remain working. To make sure a new code does what it is expected to do, we have unit testing [REF]. The unit, in this case, is a bit loosely defined as – function/method, class or module.

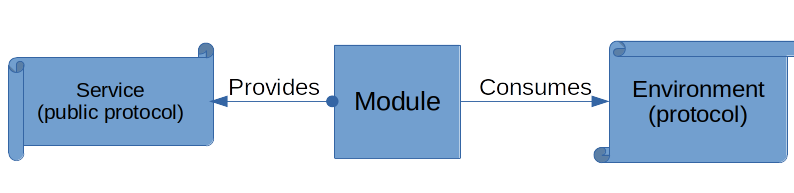

What about the interaction of features? That’s what integration tests are for. Here we test a feature or a module interacting with another module using its specification or protocol.

(A module exposes a service or a contract to the rest of the system to consume. It also may require other services to perform its function. This services are part of the module environment and consumed via their respective contract).

(A module exposes a service or a contract to the rest of the system to consume. It also may require other services to perform its function. This services are part of the module environment and consumed via their respective contract).

In other words – two sets of tests are complimentary:

- unit testing makes sure the implementation of the protocol inside the module is correct;

- integration testing makes sure a module is using other protocol to interact with other modules in an expected manner. Our module also reacts to cases defined by the said protocol.

So far, we are looking from a single module perspective – making sure it does what it says on the tin and interacts with the rest of the ‘world’ expectedly. This is great for the development phase, but how do we make sure that the world/environment is indeed what a module expects?

A real production system is quite often composed of many services. The simplest example is a web-service + database (DB) for data persistence. For such a system, we can test that all calls to the DB are logically correct and we can test that we produce expected actions when a service is triggered. What if our connection to the DB goes down? Is the service still functional? Can we say that features are usable by our customers?

Of course, the DB going down is a trivial example. Let us consider multiple services interacting - of which I have a perfect example:

On the project I worked on, the user management, and permissions management sub-systems were separate services. My team was responsible for the development and deployment of a service that consumed permission management. We deployed new versions of our service regularly, testing every new feature. One day we got a ”call’” that users could not use our service. Interestingly there were no new deployments on that day, so it could not be a new feature breaking things. We spent some time investigating what was wrong.

One benefit of dividing a system into services is the ability it gives to develop and deploy new versions of services independently. While investigating, we discovered a new version of user-management had been deployed to production a day before. It had been tested with unit tests and was working for most permission service consumers. However, that version had a bug that only affected a small set of protocol features our services used. The issues were resolved by rolling back the permission service after a lot of argument with the permissions team, whereby we needed to prove to them that their service was indeed broken.

How could this issue could have been prevented? There were two services in production, and all was working. A new version of a service A had been developed and tested. Everything was ok, so it was deployed to the production environment. Everything was still great. The team responsible for A was happy.

Team B, responsible for the permissions service, added new features and refactors existing ones. It tested everything(?), all seemed fine. It promoted the service to production, and again, everything seemed ok according to the team’s checks and tests. However, users of service A now come online and find out they can’t use A anymore. Team A is unhappy :(. Yet both services are up and running ok. They just can’t work together and as a result, end-users can’t use service A. Note that both services are “healthy” from metrics perspective: CPU and memory consumption is in check.

Does testing stop when the app is in prod?

This example brings us to an interesting point – when do we stop testing, if ever? It is understandable that as engineers, we want efficiency in our processes. Thus we wish to minimise wasteful actions. However, testing in production seems relatively inefficient. Nevertheless, our applications are, more often than not, designed to function 24x7 and always be available. Thus we need to test that they work 24x7. An alternative is to pass testing onto our customers, but they won’t necessarily be happy to take on board such responsibilities.

When we provide a service for others to consume, we create a contract that states the availability of the service. It may be implicitly stated that a user should always expect the service to be available. In this case, breaking this contract creates adverse reactions from customers. Alternatively, the contract may explicitly state the availability, for example, in a Service Layer Agreement (SLA). This is a broader topic for next time. In any case, it is the service provider’s responsibility to ensure the service’s available for customers. Automated testing in production serves to achieve this goal.

The reason I use the term “automated testing”, and not monitoring, is because monitoring does not include a notion of who triggers an action/process. For example, in the case of passive monitoring, if users never exercise a function, we won’t know whether that function is available and adequately implemented. The reason to care for such rarely-used functions is enormous; they might be for emergency use, for example: the last thing we want is for our monitoring to inform us that backup system is actually down – when we decide to restore from backups :).

Extras: capturing assumptions

There is one more benefit of creating tests for your project – it is a robust way to capture business requirements and assumptions. For example, let’s assume we have an app with private user-generated content, and we want to only allow “allow-listed” people to comment. This is part of the business proposition of the app, and it is easily testable with automated tests. Not only can we make sure this requirement is implemented, but having the test also ensures that additional features won’t break this requirement when new developers decide to change the management of permissions. If the test for this business rule is violated, the tests should fail, which should prevent us putting the broken version into production. Without these tests, the results could be disastrous; one can imagine the unpleasant surprise of app customers when after the latest platform update, they get comments on what they thought was private content. (It’s not like it never happened before: Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Google, Cloudflare, etc )

When we don’t have an exact requirement or well-defined protocol, which is often the case in start-ups that are only just figuring out their product and business rules, it may be useful to write a test to capture assumptions. This happens when a number of services constituting a system are being designed and worked on at the same time. One dev team can assume the expected behaviour of service and implement it in a test. Later on, when the service is available, this assumption can be tested by that test.

Extras 2: fixing cases and making sure they stay fixed!

It is not always possible to cover all the corner cases a system can create, and some bugs do slip through the test coverage net. This happens because systems naturally grow in complexity, and it shouldn’t make us feel defeated. We do tend to test only the cases we can predict and model. The real key here is to make sure our test coverage increases as new cases and bugs are uncovered. For example, you (or worse, your customers) have discovered a bug in the product. A normal engineering flow is to try to reproduce it, to 1. confirm there is indeed a bug, and 2. capture any relevant factors that make the issue to manifest. Once this is done, you should be able to write a test to make sure you captured the problem. The test confirms the presence of the issue. Once the solution for the issue is found, which may not happen immediately, the status of the test should indicate that the issue been fixed and you can assert that it is ‘done’. But having this extra test for a fixed problem in the codebase has an extra benefit – it makes sure the issue won’t resurface after a while. Continued improvement for the win :)

Conclusion

I took some time to reflect on the approach to testing as part of software development life cycle. Most people I talk to have a pretty good understanding of what testing is, yet when they talk about the project they are busy working on – they seems to downplay the importance of it. I believe this is due to a combination of short term perspective of SDLC coupled with our preference for instant gratification. And this is what I wanted to break down in this post. It is relatively easy to find issues early on with tests then to manually check all the business cases every time a new version is deployed.

Having good test coverage and discipline also yields extra benefits such as documentation of business rules and assumptions. Ensuring software is working is more than just writing unit tests or gathering metrics. It requires analysis of the SLA that an app provides. Of course, there is way more to the topic that I can cover in a short post so that I might return to this one later on.

Another topic I have not covered here is what we can learn from simply talking about testing with other engineers. My favourite topic when hieing engineers is to ask about their experience and approach to testing. It always yield profound insights into a person’s understanding of SDLC. Maybe I’ll cover it the next post.

What is your opinion? Where does testing sits in your development cycle? And most important: do you budget time for testing or in your organisation it is part of the normal development process? How do you make sure your application stays up and running?